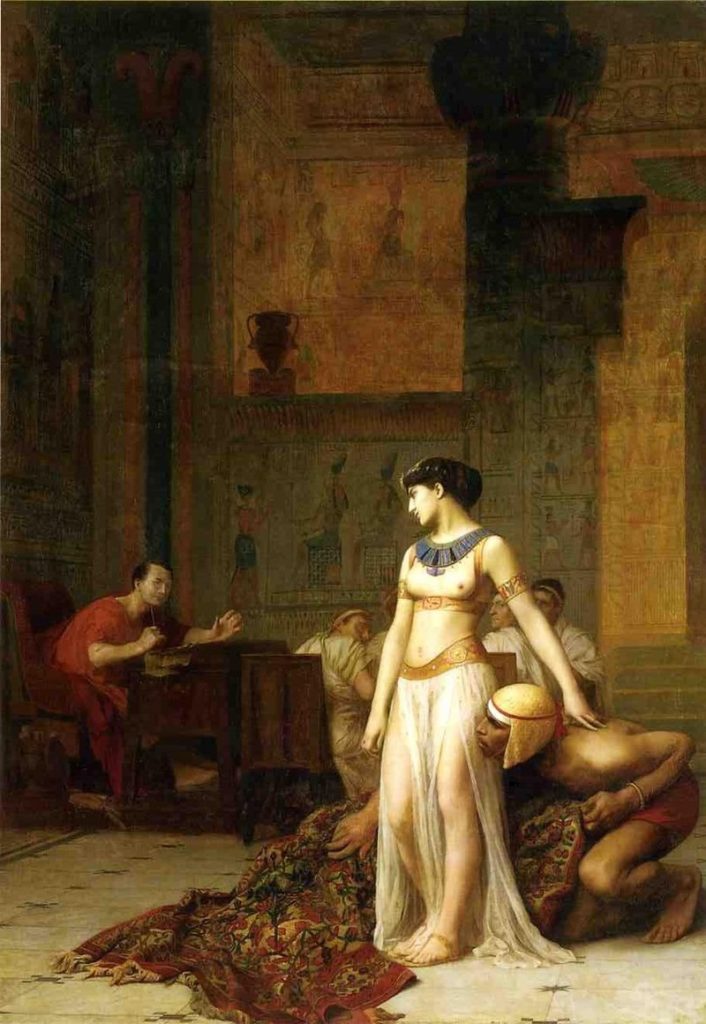

Rolled up in a carpet.

Or, by other accounts, in a sack of bed linens.

Put aside, for a moment, the legend of Cleopatra as a great seductress and think about how incredibly clever and daring that was.

Her enemies stood between her and the one person who could help her regain her throne. Enemies who would be delighted to kill her (and vice-versa, granted). The chances of battling through with an army were slim to none.

A messenger was also likely to be waylaid or killed, but her enemies had already ticked off Julius Caesar, and perhaps part of 21-year-old Cleopatra’s calculation was that they would be too afraid to tamper with a gift for him.

She could have smothered, or passed out from heat prostration. Apollodorus, the servant carrying the carpet/bedroll, could have betrayed her. Caesar’s guard might not have allowed the carpet to be carried into his room.

It was not only a once-in-a-lifetime stunt, but Cleopatra having herself delivered to Caesar rolled up in whatever-it-was, was a once-in-recorded-history stunt. Nothing like that had ever been done before, and we can be sure that from that time forward, any gifts to a ruler or conquering hero were carefully inspected, outside said ruler/hero’s presence, to make sure they did not contain an assassin, groupie or who-knows-what.

Cleopatra’s gamble paid off.

Caesar was impressed. And aroused. Whether becoming 53 year-old Caesar’s mistress to cement the deal was her idea (history has painted her as an unstoppable seductress), his (Caesar himself had a colorful sexual history as a man of many affairs), or due to mutual attraction, nine months later Cleopatra gave birth to his son, Ptolemy Caesar, who would be called Caesarion (Little Caesar).

She’d been losing the civil war; now she had Caesar and the backing of Rome on her side, who helped defeat her enemies. Later, Julius Caesar would become famous for pithily describing his conquest of Britain, Veni, vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered). As biographer Stacy Schiff put it, “Apollodorus came, Caesar saw, Cleopatra conquered.”

Caesar was then the most powerful man in the Western world, but he had his enemies. Although he sent for Cleopatra (and her son) when things “settled down” in Rome, and they continued their affair there, her presence provided a partial excuse for ill feeling against him. She was present in Rome when he was stabbed to death by the Senate, and quickly fled back to Eqypt, pregnant again with Caesar’s child, which she miscarried.

You Think Your Family Dinners Are Awkward

The enemies that Cleopatra had to sneak past while rolled in that carpet were the forces of her own brother, Ptolemy XIII. She was born around 69 BC, was named a goddess as a child, and became queen at age 18, along with her 10 year old brother as co-ruler and official husband.

Eqypt itself was heavily divided; the Egyptian people formed one faction, the Greeks who dominated Alexandria were another, and there was a substantial foreign contingent, including more Jews in Alexandria than anywhere outside of Judea itself. But the elephant in the room was the Roman empire, which dominated the Mediterranean.

Not complying enough with Rome would lead to Roman intervention; there was always the chance they would decide to replace the Ptolemies with one of their own generals, or another foreign national. Cleopatra’s uncle, the King of Cypress, had been removed by Rome. But if it appeared there was too much cooperation with Rome, the Egyptian people themselves would riot and revolt. Then there was the second elephant in the room, the not-so-happy family.

Many of the Ptolemies were stabbed, poisoned, exiled, or dismembered, most often by another family member or their agents. Cleopatra’s father, Ptolemy XII (Auletes) had been deposed by her two older sisters, and had regained his throne only with the assistance (and loans) from Rome, leaving the finances and governance of Egypt… pretty much a hot mess. Being a minor, Ptolemy XIII had a regency of three adults, while Cleopatra felt perfectly capable of ruling her country without the “help” of her husband-brother and his hostile advisers. Later, with Caesar’s assistance, Ptolemy XIII was found drowned in the Nile. Later yet, Cleopatra’s second brother became her husband and co-ruler, Ptolemy XIV, and also died young, reportedly poisoned by her.

Kind of like the George Foreman family, the Ptolemies were very big on using the same names, over and over again.

When people talk about Cleopatra, we almost always usually mean the last pharaoh of Egypt, who technically was Cleopatra VII Thea Philopater. Although the first Ptolemy was a Macedonian Greek general under Alexander the Great, who liberated Eqypt from Persian rule in 332 BC and founded the city of Alexandria, it’s not only hard to tell the players without a program, it’s hard to tell the players with a program. Then there’s the whole Eqyptian royalty tradition of pharoahs marrying sisters/mothers/aunts, which the Ptolemies adopted.

As demonstrated by “our” Cleopatra, simply because a pharoah was officially married to a sibling (or two), or other relation, that does not necessarily mean the official spouse was the father or mother of one’s children. Cleopatra would later name her son Caesarion her co-ruler as Ptolemy XV.

The Lips That Launched A Thousand Ships

One feature on which everyone agreed was Cleopatra’s “most charming voice and knowledge of how to make herself agreeable to everyone.” (Cassius Dio) She had charisma, she was fluent in at least seven, by some accounts, nine languages, and she was quick-witted. Plutarch says:

“For her beauty, as we are told, was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her; but converse with her had an irresistible charm, and her presence, combined with the persuasiveness of her discourse and the character which was somehow diffused about her behaviour towards others, had something stimulating about it. There was sweetness also in the tones of her voice; and her tongue, like an instrument of many strings, she could readily turn to whatever language she pleased…”

Her ability to converse with just about anyone in his or her own language, was an invaluable tool for a Queen who had to win her way through diplomacy, rather than force of arms. Egypt, before and during Cleopatra’s time, had little in the way of standing armies. What Egypt was famous for, however, was shipbuilding (as makes sense for countries engaged in international trade). While Mark Antony was vilified by Rome for assigning various timber-rich provinces to Cleopatra’s care, it makes sense since she had the tradesmen and resources to transform trees into a sizable navy.

She was the first Ptolemy to learn the Egyptian language; all others had stuck to Greek.

But was she beautiful? One controversy raging in modern times is whether Cleopatra was black – or was not black. and what she actually looked like. The coins and busts that remain depict her as having a rather prominent nose, and a firm chin, though they may or may not be actual likenesses. I’ve read various opinions that depict Cleopatra as brunette, blond, redheaded, olive-skinned, pale-skinned, dark-skinned. For now, the jury is still out on that issue; we know she had Macedonian Greek

ancestry, she was an African queen, and much of her genetic heritage is unknown. There was certainly prejudice and discrimination in those days, but it was not based on skin color.

Cleopatra probably didn’t look much like Beyoncé or Elizabeth Taylor, although thanks to this movie, Liz represents the mind-picture many of us form of her.

What the 1963 movie, which was at the time the most expensive movie ever made, portrays well, is the pageantry and excess of both Egypt and Rome of that era. There are many historical facts it plays fast and loose with, but Cleopatra’s grand entrance into Rome is not-to-be-missed. No CGI in those days, it cost a mint to build, costume, and film.

Alexandria was the New York City of Its Day; Rome was More Like… Albany

Near the mouth of the Nile, Alexandria was a trading port in a prime position. A new city, expertly planned, it boasted broad, clean streets, stadiums, baths, gymnasiums, concert halls, and running water in the houses. Alexander the Great’s body was entombed there; the 370+ feet tall Alexandria Lighthouse was one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, and then there was the Alexandria Library.

The Alexandria Library contained over 500,000 volumes, with attached lecture rooms and exhibition halls. It became the world’s first true university, where astronomy, geography, physics, mathematics, zoology, language and literature were taught. They figured out that the Earth and other planets circled the Sun long before Copernicus “discovered” it.

Julius Caesar himself is said to have accidentally burned part of the Library during what became known as the Alexandrian War, his defense of Cleopatra’s throne against her younger brother and sister. The rest of the library may have been destroyed by Emperor Aurelian (3rd century AD) and by decree of Emperor Theodosius (391 AD), because, well, pagans.

Can we have a moment of respectful silence for the Alexandria Library, please?

The Ptolemies were the original book thieves. Any ship coming into Alexandria harbor was searched for books (then in scroll form), and said books confiscated. After being taken to the library and carefully copied, the book copies would be returned to their owners.

Rome, in contrast to Alexandria, was primitive, crowded, and noisy. The Roman crowds loved spectacles (bread and circuses) and the Triumphs held by the conquering generals, usually featuring captured enemy combatants. Caesar himself held three Triumphs while Cleopatra was his guest in Rome, including one about the Alexandrian War. Even though her sister Arsinoë had revolted against her, seeing her paraded past the roaring Roman crowds wearing silver chains left an indelible impression on Cleopatra.

While Roman armies were out conquering the world, the Roman government itself was in a constant state of flux. Rome had been a Republic, then Caesar was chosen as Dictator for Life. After Caesar’s murder by the Senate, there would be a Triumvirate: Octavian Caesar, who was Julius’ adopted heir, Mark Antony, and Lepidus.

Mark Antony – Not The Sharpest Sword in the Armory

He was a dear friend of Julius Caesar, and had won some important military victories. He was also something of a party animal, perhaps even an alcoholic. When he and Cleopatra began their affair, it is possible they were truly in love. It is also possible Cleopatra coolly surveyed her options for the best possible Roman alliance to protect Egypt: Lepidus, already being edged out of power by Mark Antony and Octavian; Octavian – the adopted son of Julius Caesar, a natural rival of Cleopatra’s son by Julius Caesar, and decided that Mark Antony, weak reed that he was, was her best option.

It is from her time as a lover-wife of Mark Antony that some of the most extravagant tales of Cleopatra come: the golden barge with purple, perfumed sails; the swallowing of a pearl (after pretending to dissolve it in vinegar; clever Cleopatra knew vinegar didn’t dissolve pearls); the fishing trip where, after Antony was faking a catch by having swimmers place purchased fish on his lines, she one-upped him by having a purchased, salted fish placed on his hooks. The revels and ceremonies with herself as Isis/Aphrodite, and Antony as Osirus/Dionysus. The three children she bore: twins Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus.

In a culture where Roman women did not even have the right to their own names: Julius Caesar’s daughter was Julia, Octavian’s sister was Octavia, Mark Antony’s daughters were all Antonia; the idea that Cleopatra, a woman, was a political force to be dealt with put Roman togas in a twist. So it was easy for a devious plotter like Octavian, who played the long game, to plant seeds of disaffection among both Antony’s partisans in the Senate, among the Roman people, and even among the armed legions. It didn’t help that to Roman eyes, Antony was “giving away the store” in terms of eastern possessions to Cleopatra and her children.

In the end, Octavian ‘s admiral, Agrippa, defeated Antony and Cleopatra’s fleet in Actium, Greece. Octavian persuaded Antony’s legions to desert to him in droves, and had both Cleopatra’s son Caesarion, and Antony’s oldest son, Antyllus, murdered.

All that was left was to drag Antony and Cleopatra back to Rome to walk in chains at his Triumph.

Death Can Be a Pain in the Asp

Mark Antony, after living in shame for some months after Actium, finally determined to kill himself, but managed to bungle that, too. He fell on his sword, but took long enough dying that he could be brought to Cleopatra where she had holed up in her mausoleum.

After arranging Antony’s funeral, Cleopatra, who had long decided that she would not do the Roman Walk of Shame wearing Chains, in silver or any other color, was ready to take herself out in style. Unlike Antony, she wasn’t going to bungle it. She had laid in a supply of poisonous snakes – or poisoned figs, some historians believe – and managed to sneak them past Octavian’s clueless guards. Enough for herself, and for her two closest handmaidens, Charmion and Iras, who also preferred to take themselves out, rather than trust themselves to Octavian’s mercy.

As last step, Cleopatra sent a letter to Octavian, requesting burial in Antony’s tomb. He sent guards to stop her, but they arrived only in time to see Iras and Charmion die.

Charmion was adjusting Cleopatra’s crown. “Was this well done of your lady, Charmion?” he was supposed to have demanded.

“Extremely well,” she said, “as became the descendant of so many kings.”

After an ending like that, Cleopatra’s life and death has been told, retold, dramatized by Shakespeare, made into many movies, and painted by… pretty much everyone. Cleopatra lived her life on her own terms, successfully ruled Egypt for almost twenty years, and died on her own terms, at the age of 39.

From Smithsonian Magazine, Rehabilitating Cleopatra by Stacy Schiff:

…Catastrophe reliably cements a reputation, and Cleopatra’s end was sudden and sensational. In one of the busiest afterlives in history, she has become an asteroid, a video game, a cigarette, a slot machine, a strip club, a synonym for Elizabeth Taylor. Shakespeare attested to Cleopatra’s infinite variety. He had no idea.

And coming soon, a new movie about Cleopatra, starring Israeli actress Gal Gadot (Wonder Woman), to be directed by Patty Jenkins, and written by Greek screenwriter Laeta Kalogridas. “…in a way she’s never been seen before.”

For More on Cleopatra:

Cleopatra, A Life – Stacy Schiff (non-fiction)

The Memoirs of Cleopatra – Margaret George

Cleopatra’s Clothing – David Claudon website

Cleopatra – Empress of the Nile – Ron Miller and Sommer Browning

History Channel Documentary

About the Great Sluts in History series:

What makes a woman a “slut,” anyway? From Lillith to Jezebel to Sandra Fluke, it seems that whenever women are in positions of power, open about their sexuality, “too outspoken,” or heaven forbid, all three, they are labeled sluts by some men (and sometimes other women), in an attempt to shame them into “knowing their place.” And into meekly accepting “their place.”This series will look at flawed and wonderful heroines throughout history who insisted on “Following their own weird,” no matter how much it cost them to do so. And how, by doing so, they made the world better for all humans, of all genders, who followed them.

“…it is no longer acceptable to discuss women’s rights as separate from human rights… If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights, once and for all.” ~Hillary Rodham Clinton, 1995

This is an updated version of the Slut essay originally published on my blog in 2013.

What have you always “known” about Cleopatra – and what has surprised you?

Do you have a favorite Cleopatra book or movie?

Your thoughts?

I have recently started a blog, the info you provide on this website has helped me tremendously. Thanks for all of your time & work. Ora Jesse Curtice