I’m not a nurse or a doctor or a chaplain. I’m a writer, when I can find the time, and my day job is working in the business management division of an accounting firm.

Turned out, my skills, my own experience with and knowledge about breast cancer, and my friendship, helped her go out on her own terms.

Most of us are uncomfortable thinking or talking about death. We know we’ve got to die, someday, we know that people we love are going to die, someday, but talking about death, planning for death, is taboo for the most part. It’s like Death is a bill collector; we think if we pull the shades and don’t answer the door, we can postpone dealing with it forever.

Except, of course, we can’t.

When my friend, who’d been diagnosed and treated for “triple negative” breast cancer in August 2017, reported to me in March 2019 that she was going to see a doctor because of serious pain in her elbow joint, and also, mysterious bumps on her head, plus other ailments, she was worried that her cancer had returned, and metastasized.

It had. In a matter of weeks, she went from being able to walk five miles a day, feeling strong and well, to being disabled and requiring 24/7 care to eat, bathe, and dress.

She wanted to use California’s Death With Dignity Act. Would I help her?

Death by cancer can be one of the ugliest, most painful, and dehumanizing ways to leave this life. Having witnessed my mother die that way when I was a child, I support anyone who wants to “take the shortcut.” My friend was a widow with no children, and her extended family simply didn’t have either the time or the emotional fortitude to help her. She knew that it was asking a huge thing of me.

Of course, I said yes. But I didn’t realize how intense a period of mental, physical and emotional labor I was going to be dealing with.

Here’s some of the things I learned:

1) Even if you are dying of cancer, that doesn’t mean a hospital can find you a bed. If they do find you a bed, on a temporary basis, you still can’t stay in the hospital unless you are within days or hours of death. My friend used the hospital as a temporary stopgap so that she could meet with the hospice team who would be helping her, and to allow time for us to set up the 24/7 nursing care she needed.

2) Many hospice teams are affiliated with religious organizations that oppose the principle of Death with Dignity, so you have to make sure that your doctor: 1) is onboard with your plan, and 2) can connect you with a hospice organization that will help carry out your wishes.

3) Wills, Trusts, and other Estate provisions. Are they set up, have they been recently reviewed, and any necessary changes made?

4) Have you designated a Medical POA (Power of Attorney), in case you can no longer express your wishes? Have you indicated DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) on all your forms?

5) Have you picked a mortuary or other organization and decided what you want them to do with your body?

a. Burial — You’ll need a plot, and possibly a vault in addition to a casket or two. Fun fact: families can RENT a fancy casket for a viewing or funeral, and transfer the loved one to a less expensive casket to be put into the ground.

There are also a handful or organizations now offering what they call organic funerals, where people are buried with the intent of natural decomposition.

b. Cremation — you also need to choose a box, anything from fancy (again, one can be rented for a viewing or funeral), to simple wood, to a cardboard box. External metal (earrings, piercings, hearing aids, etc. need to be removed, and the mortuary should be alerted as to any internal metallic devices, like pacemakers.

What will happen to the ashes? Scattered in a meaningful place? In an urn on somebody’s mantel? Interred in the ground or in a columbaria? (A wall holding urns of many people.) If the ashes are going into an urn, what do you want the urn to look like, and will it fit in the columbaria? (FYI, you can buy an urn on Amazon.)

c. Donation — Some people are choosing to donate organs, and/or whole body donation for medical research and practice by medical students. Usually the family can opt to have ashes returned — or NOT returned. What would your preference be?

To qualify for Death with Dignity, in California, according to present law:

6) Person must be diagnosed as having less than six months to live, by an oncologist or other medical doctor AND have been a resident of California for at least six months, prior to the diagnosis. (So, no “death tourism.”).

7) Person must ASK their doctor to start the process. Then, no sooner than two weeks from the first discussion, they must have a second discussion with their doctor. (Can be via phone.)

8) There must be a consultation with another doctor, who cannot be a colleague or association of the first doctor, and the second doctor must also concur that the person has less than six months to live.

9) If there is any doubt that the terminally ill person is making the decision on their own — for example, there might be pressure from the family to not run up medical bills — there must be a consultation with a psychologist to ensure they are making the decision of their own free will.

10) Steps 3–5 have been completed.

11) The doctor can then order the end-of-life prescription. It can take several days for the medication to be delivered; it’s not something they stock at CVS or Walgreen’s.

12) The dying person must give her hospice team at least 48 hours heads’ up, if she would like them to be present.

13) The dying person MUST be able to ingest the medication, which will be presented as a bitter liquid, by themselves. They can use a straw, but no one can hold the cup for them, or lift it to their lips. They have to drink it all, about four ounces, within 1–2 minutes, or there is the danger it will simply cause unconsciousness.

My friend was terrified that she would pass the point of no return, that is, her cancer would render her unable to self-administer the meds. The cancer was disabling her so fast. One arm was wholly disabled, and she began experiencing pain and shakiness in the other arm.

But the waiting period gave us an opportunity to talk, and to make the kinds of arrangements she wanted. A niche in a columbaria near her father, on the other side of the country. She was able to make some of her goodbyes in person, and as for others, in her final weeks, she became overwhelmed trying to communicate via phone and email. With her dominant hand disabled, and her secondary hand shaking, the “helpfulness” of autocorrect and constant robo-calls drove her to tears.

She decided what would she wear, when crossing over to the other side, and who did she want present in her final hours?

In the hours we spent together, a lifetime worth of tales poured out of her. I was glad to listen to the stories she needed to tell, and at her request, read to her several nights a week from her favorite book. She was so brave. Sometimes there were tears and emotional meltdowns, which she always apologized for. I thought she was entitled to them, and sometimes the tears were mine, too.

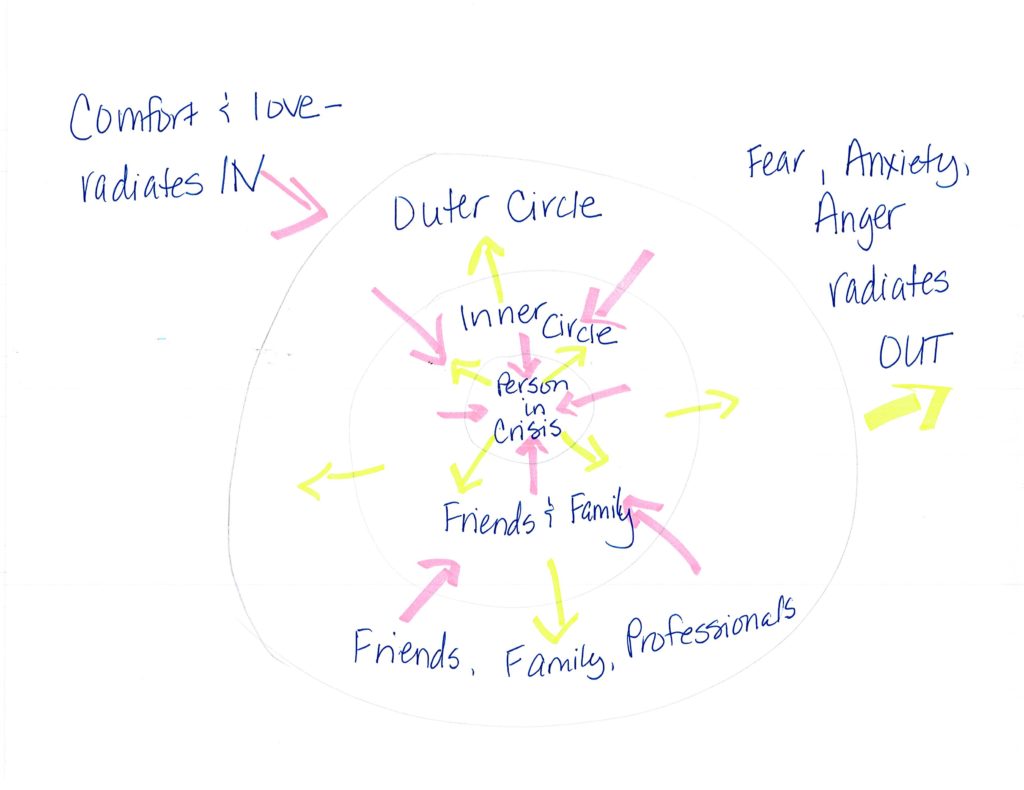

During this time, I got wonderful emotional support from friends and lovers who gave me everything from amazing massages, to a day in a virtual blanket fort. I once saw a really good illustration about how, in crisis, the fear/pain/anguish needs to radiate OUT from the person in crisis, and what comes IN needs to be love, support, comfort. Below is my shitty attempt at recreating the illustration.

It took less than six very full weeks from her terminal diagnosis, to the time her pain had grown so intense she was ready to go, and that was only a few days after the end-of-life medication had been delivered. When the day came that she had selected, I had soft music playing in the background, including some of her favorite songs, as she’d requested, and put out a single white rose, her favorite. I also found her childhood teddy bear and put him in her arms, which made her smile.

She had to swallow two anti-nausea meds, about an hour before the megadose of morphine that would end her life. Then she downed the morphine mixture. She was so determined to finish it all, the straw made that “sucking” sound in the bottom of the cup. And smiled. “That was the easiest part of all of this,” she said. With her best friend on one side, me on the other, and her caregivers and hospice team gathered around, telling her how brave she was, and giving her our love, she “went” quickly and painlessly, as she’d hoped. I think her very last words were “I love you.”

Her caregivers tenderly washed her, dressed her in the pretty silk pajamas she’d chosen, put lipstick on her, and her teddy bear back in her arms.

I stayed after her hospice nurse and caregivers had left, while she, and later, the medical equipment, was picked up. I have been at deathbeds before, and saying goodbye to people we love for the rest of this life will never be easy, but I had never done anything quite like this before. I am honored and glad I was able to help my friend, I feel pride and relief that I didn’t screw things up (and a bit of anger at Forest Lawn, who did screw a number of things up).

And I feel sad, because I miss her.

A few weeks later, I still feel very “full,” emotionally, and wish we could give everyone the kind of end of life transition they want.

Beverly, I am quite blown away by your blog/writing. (I just commented on the breast cancer recurrence post – found you on Women in Midlife). My sister desperately wanted to end it in NC. There in her refrigerator was the morphine, supplied by hospice for palliative care, but she couldn’t get out of bed to get it, and I couldn’t give it to her (neither she nor I wanted me to risk criminal charges.) For five months I shuttled back and forth between Florida and North Carolina, seeing her misery, her inability to control anything, her rage (sometimes at me). We had some good times in that time, but it was terribly cruel. It’s been two years, I miss her every day. Your friend did a wise thing (so did the CA legislature) and you did a good thing.

I have subscribed to your website – you are a pisser. Please take a look at mine. elizabethmccullochauthor.com

I am so sorry your sister’s end was rough, but good for you for taking the best care of her you could.

I think the dying process is especially hard for those who are used to being in control of all the things in their own lives. (It’s also not easy on those of us watching a loved one suffer.)

Sending peace and healing to you.